By PHILLIP BANTZ

Sentinel Staff

The Keene Sentinel: March 12, 2010

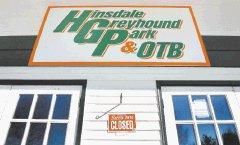

MANCHESTER — Surrounded by three lawyers, the man who ran the now-shuttered Hinsdale Greyhound Park walked out of U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Manchester Thursday afternoon, closing the door on a Chapter 7 case that began in December 2008.

Joseph E. Sullivan 3rd declined an interview request through one of his attorneys, Arpiar G. Saunders Jr., after the hearing. Sullivan believes the “court order stands for itself,” Saunders said.

In the order, Chief Judge Mark W. Vaughn called the bankruptcy settlement “fair and reasonable and in the best interests of the bankruptcy estate.”

The settlement Vaughn approved calls for drawing $1,086,120 from the estate to repay the track’s creditors.

Dozens of bettors who were unable to withdraw their wagering accounts when the track closed stand to be repaid about half of what they’re owed, said Deborah Notinger, an attorney for the bankruptcy trustee, Michael S. Askenaizer. The court appointed Askenaizer to liquidate the track’s assets.

One of the track’s biggest bettors, Herschel Bird of Nevada, disapproves of the settlement. He suspects that Sullivan, who had a salary of more than $200,000 during the three decades he ran the track and took out $650,000 in loans from the business, may have hidden assets from Askenaizer.

“When you’re asked to take 50 cents on the dollar, you feel like you’re being ripped off,” Bird said. “Something doesn’t ring true about Sullivan’s finances.”

Sullivan stated in a deposition with Notinger that he is destitute and financially dependent on his sister, who loaned him $70,000.

Sullivan and his wife own a house and two properties in Swanzey valued at an estimated $575,000.

But after a $375,000 mortgage, they have about $200,000 in equity in those assets, according to Sullivan’s deposition.

Sullivan also lists $123,206 in other personal property, which includes a 2003 Cadillac Seville, a 2004 Jeep Cherokee, jewelry and art.

Based on the advice of his attorney, Bird did not file an objection to the settlement with the court, which might have altered the outcome of Thursday’s hearing. None of the track’s other creditors objected to the deal.

Under the settlement, $400,000 will be taken from the proceeds of a land deal Sullivan and business partner Carl B. Thomas, who owns Spofford-based Thomas Construction Corp., made with Wal-Mart Stores Inc. Sullivan has to come up with another $400,000 by selling the remaining former track land.

That land, about 66 acres, belongs to Hinsdale Real Estate LLC, a holding company Sullivan and Thomas created before the bankruptcy filing.

Sullivan sold the track land, originally 91 acres, and buildings to the holding company for $3.3 million.

Later, the holding company sold 25 acres to Wal-Mart for $2.1 million. The remaining 66 acres have been assessed at $1.2 million. The buildings on the property are assessed at $3.5 million.

Sullivan disagrees with those assessments. He has made an unsuccessful attempt to have Hinsdale lower the assessed value of the land and buildings, which would result in a decrease in property taxes. He is appealing the town’s decision to the state.

Sullivan and Thomas have two years to hand over $400,000 to the bankruptcy estate by selling all or some of the 66 acres at and around the track before the court steps in and forces an auction of the property.

The $800,000 from that land sale and the Wal-Mart deal will be combined with $286,120 the bankruptcy estate has from the track’s other liquidated assets, such as computers, furniture and vehicles that were auctioned last spring.

A peripheral condition of the settlement calls for Thomas to buy Sullivan’s 75 percent interest in Hinsdale Real Estate for $500,000.

Sullivan owes Thomas about $2.3 million for two loans secured by mortgages tied to the former track property. Thomas is gambling that he can recover his debt on the mortgages and perhaps make a profit by selling the 66 acres, even after the court takes a $400,000 cut from the proceeds.

“That land is worth bupkus. Nothing’s selling in that area,” Notinger said after the settlement hearing. “He’s taking all the risk and we’re getting money up front.”

Askenaizer and Notinger have raised concerns that Sullivan’s deal with Hinsdale Real Estate prior to the bankruptcy filing was a fraudulent property transfer.

But they agreed in the settlement to not pursue the allegation by filing a lawsuit against Sullivan.

They say legal action would be expensive and, even if it were successful, Askenaizer would be responsible for selling the track’s remaining property to pay off Thomas’ debt and the creditors.

Bird, the Nevada bettor, criticizes Askenaizer and Notinger for being too passive in their handling of the track’s bankruptcy — he wanted them to thoroughly investigate Sullivan’s finances instead of relying on the deposition and his financial affidavit.

Bird wants to know what Sullivan did with the money he made while working at the track and the $650,000 in loans he took from the business. Sullivan’s two daughters were also on the track’s payroll for years, making about $25,000 annually, even though they did not hold regular jobs, according to two former track employees who asked to remain anonymous.

In his deposition with Notinger, Sullivan indicates that he used a portion of the $650,000 that he took from the track to correct accounting errors.

Sullivan said the track’s vice president of operations, whom Sullivan appointed to run the company for a stint in 2005, had a gambling problem and used company money to fuel his addiction.

“When I had to let him go I went back in and the accounting was a wreck and I set about rebuilding it,” he told Notinger.

One of the former track employees wrote in an e-mail that Sullivan “representing himself to be ‘the cavalry’ riding back in to put (Hinsdale Greyhound Park) back in operating order after less than a year of mismanagement is bull crap. Joe never stopped controlling operations at HGP, he just hid in the shadows.”

Meanwhile, Bird said the track’s creditors may have gotten a raw deal because the bankruptcy trustee system is flawed. He said trustees have a financial incentive in the outcome of Chapter 7 cases in which assets are available to liquidate, which rarely happens.

Trustees receive a percentage of the funds they gather for the bankruptcy estate based on a sliding scale that ranges from 25 percent for the first $5,000, 10 percent for the next $45,000, 5 percent for the next $950,000 and 3 percent of the balance. They can also be paid for legal services.

The amount of Askenaizer’s payout was unclear and he did not return a phone message before press time today. An attempt to reach Notinger was also unsuccessful.